Silicon Valley has changed. There are far fewer semiconductor startups now. Almost all the fabs are gone too. The one startup who was brave enough to build a new fab prominently in Silicon Valley shut its doors last week. We had a Hollywood style FBI raid on the premises soon after to make things more dramatic. Yes, I'm talking about Solyndra. On another note, Marc Andressen, the founder of Netscape and now a venture capitalist and board member at HP, wrote an excellent article for the Wall Street Journal titled "Why Software is Eating the World". It came soon after HP announced it was jettisoning its hardware businesses last month. Should we rename Silicon Valley and call it Software Valley? Or is there hope for semiconductor startups still?

A panel of high-profile VCs, Investment Bankers and Executives debated this very question last week. It was a fantastic event - the panelists showed concrete data on various phenomena, and shared their experiences and insights. The members of this august panel were:

The panel offered perspective from many angles: Andy Rappaport and Lip-Bu Tan are well-known VCs, Charles Welch is an expert in semiconductor Mergers & Acquisitions, Adam Howell specializes in Semiconductor IPOs while Ralph Schmitt has been a CEO of many semiconductor startups.

Here's what the panel said:

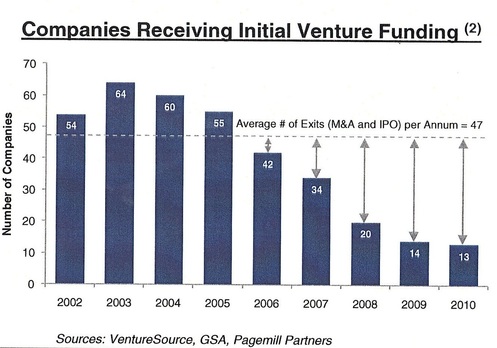

Is the number of semiconductor startups really going down exponentially?

Yes, the talk we keep hearing in Silicon Valley coffee shops is true :-( Below is data collected by Page Mill Partners. This trend is not because of lack of ideas, but because investors have been moving to other areas such as software and cleantech. Gartner projects that the semiconductor market will show a CAGR (Cumulative Annual Growth Rate) of 6.2% between 2010 and 2015, so we know that the overall market is not shrinking, even though the startup scene is.

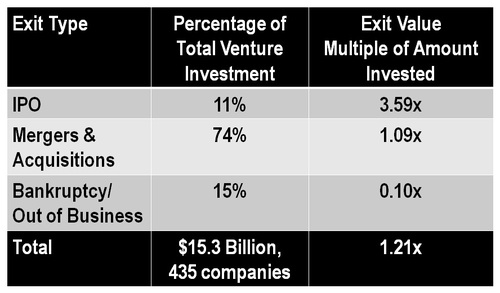

What are the returns for semiconductor startups between 2002 and 2010? Are they low? Is that one reason why the investors are going away?

The table below from Page Mill Partners answers this question. You'll see a 3.59x Return on Investment (ROI) for IPO companies, which account for 11% of venture investment. Most semiconductor startups end up being acquired with a 1.09x ROI. The overall ROI for semiconductor companies is positive. The Investment Bankers on the panel said this was not bad, but Andy Rappaport, a VC on the panel, said that the 3.59x ROI they get for semiconductor IPO companies is not good considering the risk they are taking and the high amounts they need to invest. Andy Rappaport, who manages a $650M VC fund, said for him to get value on a semiconductor startup, it needs to become a $1B company within 5-10 years. Converting $10M to $40M doesn't make a significant dent on his fund, he said. He mentioned that it is almost impossible to build a startup that can achieve the billion-dollar scale in semiconductors anymore with less than $100M investment, and have this startup surprise existing players in the market :-( He said the only semiconductor startup that has done this in the past 10 years is Atheros. While Andy Rappaport seemed pessimistic about semiconductor startups and other panelists said this is the dominant opinion in the VC community, Lip-Bu Tan, the other VC on the panel, said one can get a good ROI on semiconductor startups using some interesting and unique strategies. I will bring up Lip-Bu Tan's points later in this article.

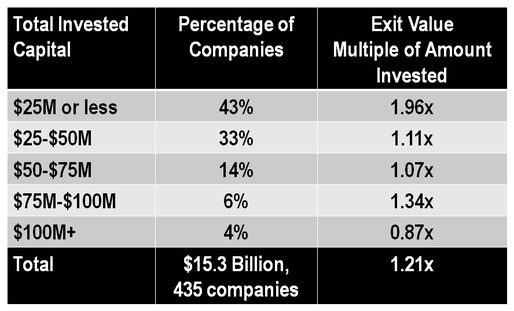

The data below from 2002-2010 shows that startups that require less capital typically give a larger ROI. Both VCs on the panel said they would not invest more than $50M on a startup, since the risk to their VC fund was too high. Lip-Bu Tan said his sweet spot is to invest $40M on a startup, and see it converted to $300-500M. He said many mixed-signal startups require that level of investment, which he is ok with. Both VCs on the panel said the glory days of Digital SoC startups are gone since they require more than $100M of investment.

According to Lip-Bu Tan, his VC fund has 25-35% of its investments in semiconductors. They get a 2.5x-3x ROI on this portfolio, which is a lot higher than the 1.21x seen by the average VC fund. One of the key strategies they use is cross-border investment. Lip-Bu Tan said the market for semiconductors in China is $110B, of which less than 5% is produced within the country. The Chinese government has made development of the local semiconductor industry a key priority and is willing to put in an unlimited amount of investment, according to him. Many of Walden's startups partner with the Chinese government, have a significant presence in the country, and get large grants from the government for their development. This makes their value proposition a good one. The Chinese government, for instance, has put in huge amounts of money into SMIC, and Lip-Bu Tan is a Board Member there. As one can imagine, Walden's strategies are a function of their contacts in China and cannot be reproduced easily by others.

Considering this scenario, is the IP business model a viable one for semiconductor startups? Will it keep the costs under control and boost the chances of getting a reasonable ROI?

This was the question I asked the panelists once they gave their prepared statements. They came up with an interesting set of answers.

Lip-Bu Tan: Yes, I believe the IP business model is promising. That's one of the reasons why I purchased Denali while serving as CEO of Cadence. Operating margins are greater than 35%, which is great. Companies such as ARM have shown the IP model can be quite rewarding.

Andy Rappaport: Yes, I also feel the IP model is viable. In fact, back in the 1990s, Silicon Architects, which was one of my startups, used the IP model. It was sold to Synopsys in the mid 1990s. This being said, I don't think the IP model necessarily lowers costs. To sell IP, you need to invest money in building state-of-the-art prototypes, which can be almost as expensive as selling products. The only companies that have been successful at selling IP are those who do it because it is a natural fit to their business and not because it is cheaper. Rambus and ARM are good examples.

Adam Howell: Companies such as ARM are valued at $12B now, showing that the IP model works. That being said, only a small percentage of semiconductor IPOs are IP companies today, indicating the model is not easy to reproduce.

There were a lot of other interesting things said on the panel, but this post is getting long, so I'll finish up now. The key message from the event was this: The bar for semiconductor startups is a lot higher today than it was 10-20 years back. Entrepreuneurs need to think creatively about their business models to make semiconductor startups viable, and not limit their creativity to technical aspects alone.

- Post by Deepak Sekar

RSS Feed

RSS Feed